Earlier this week, health officials in the US state of Oregon confirmed the first case of bubonic plague since 2005. According to reports, the person who contracted the disease likely got it from a sick pet cat.

The disease was quickly detected, and the individual received antibiotics for treatment. Health workers also tracked down and treated those who had been in contact with the person and the cat. Unfortunately, the cat did not survive despite receiving treatment.

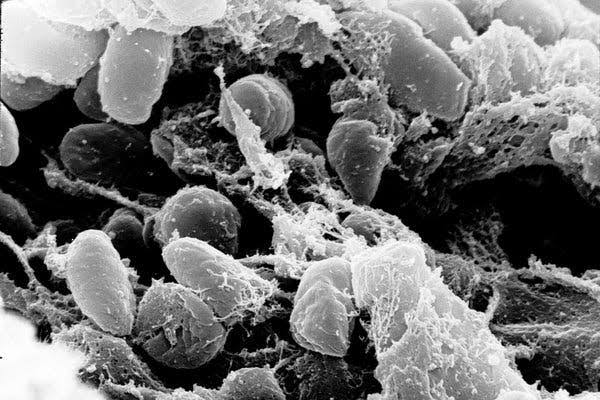

The bubonic plague is caused by Yersinia pestis, a type of zoonotic bacteria that can spread between animals and people.

Y. pestis is typically found in small animals and their fleas. Humans can contract the plague in one of three ways: through the bite of infected vector fleas, through unprotected contact with infectious bodily fluids or contaminated materials such as being bitten by an infected rat, or through the inhalation of respiratory droplets or small particles from a patient with pneumonic plague.

Bubonic plague specifically refers to cases where the bacteria enters the lymph nodes. Symptoms include fever, headache, weakness, and painful, swollen lymph nodes. It usually occurs as a result of being bitten by an infected flea.

Septicemic plague happens if the bacteria enters the bloodstream and often follows untreated bubonic plague. This type of plague can cause additional, more severe symptoms such as abdominal pain, shock, bleeding into the skin, and blackening of appendages, most often fingers, toes, or the nose. This type comes either from flea bites or from handling an infected animal.

Pneumonic plague is the most dangerous form and is almost always fatal if left untreated. It occurs when the bacteria enters the lungs and adds rapidly developing pneumonia to the list of symptoms.

This is the only form of plague that can be transmitted from person to person by inhaling infectious droplets, making it the most contagious.

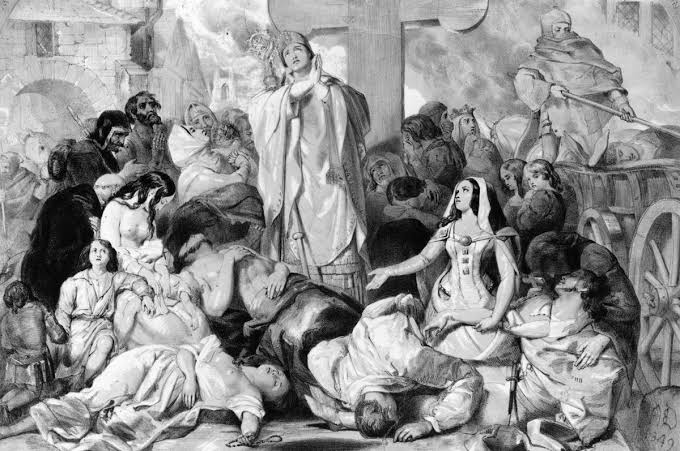

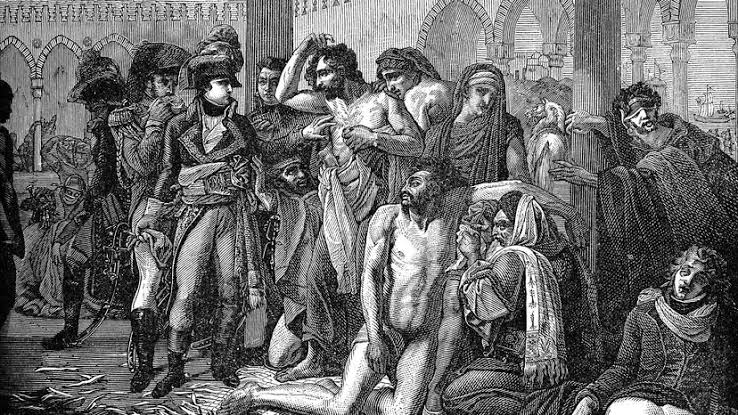

Between 1346 and 1353, the bubonic plague killed as many as 50 million people in Europe, an event now known as the Black Death. Although the latest case of bubonic plague discovered in Oregon is not a cause for concern, the Black Death was the single deadliest disease outbreak in history, having wiped out up to half of Europe’s population.

As a result, it left a lasting impact on the survivors, with certain genetic mutations increasing their chances of survival by around 40%. Unfortunately, these mutations have since been passed down and have been directly linked to the incidence of certain autoimmune diseases.

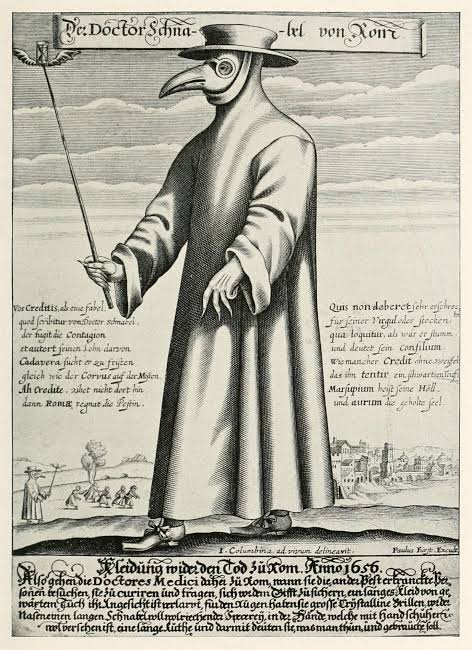

Despite Y. pestis being able to occur virtually anywhere and potentially being fatal to individuals, there is no need to worry about another Black Death.

Modern antibiotics are highly effective against Y. pestis, and better hygiene and understanding of the disease have significantly reduced the number of cases reported each year. According to the CDC, all forms of the plague are treatable with common antibiotics, with early treatment drastically improving chances of survival.

While there may be isolated cases of the plague, a larger pandemic similar to the Black Death is highly unlikely.