recently, the govt introduced and passed the Criminal Procedure (Identification) Bill within the Lok Sabha, seeking to switch the Identification of Prisoners Act, 1920 which regulates how the police can gather data from convicted or suspected criminals.

The Bill exemplifies the present trend to pass laws that are crammed with ambiguity and lack safeguards. It also reflects a desire to expand the facility of the govt. to interfere with the lives of citizens.

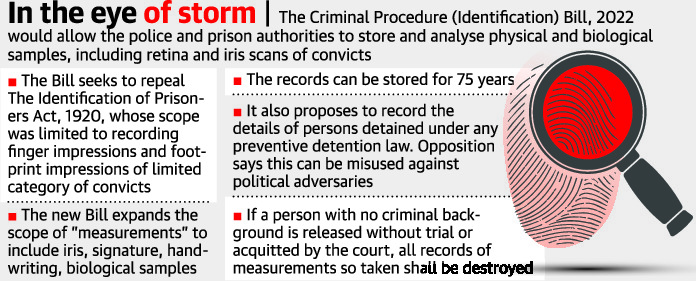

The Bill was passed, the kind of information collected by the police would shift dramatically, from basic fingerprint and footprint impressions to a variety of other samples, including iris and retina scans, behavioural attributes, and “biological samples”. The National Crime Records Bureau would hold the collected data for 75 years.

Rule-making power during this arena, currently vested only in state governments, would be extended to the central government. More importantly, the Bill would entirely reshape the remit of law-enforcement officers to collect personal data.

While this law’s provisions apply only to convicts, people who are out on bail or those arrested for serious crimes, the Bill extends this wanton collection of knowledge not only to all or any convicts, but also to anyone who is arrested or detained, and even those that are merely “suspected” of committing a criminal offence or are deemed “likely” to try to so.

It is common enough for law-enforcement agencies the globe over to gather personal data from people they arrest and convict. But two issues particular to the Indian context make this Bill disturbing and wired.

First, the govt of India has repeatedly demonstrated a crippling fear of dissent and a willingness to wage open warfare against its opponents – presented, lately, as enemies quite adversaries. If the Bill was so implemented or enacted, nothing would stop the police from, say, detaining protestors and collecting their personal data to use against them at a later date.

Considering the way enforcement has used such methods in the past, notably against crowds who were peacefully protesting the Citizenship Amendment Act in Delhi and the province in 2019-20, such a law would encourage this type of behaviour, and further erode the already scant safeguards that exist against the government’s intrusion into citizens’ lives.

The Bill’s widening of the current law’s scope, giving the police the freedom to assemble personal data from more or less anyone they choose, proves that this fear might not be unfounded.

Second, India’s privacy rules are threadbare. The GoI’s casual approach was last exemplified by the controversy surrounding the paucity of safeguards built into Aadhaar, similarly because of the numerous failures of the Aarogya Setu contact-tracing app.

Although the Supreme Court’s Puttaswamy decision in 2017 established privacy as a fundamental constitutional right, the method to draft and introduce national data protection legislation has dragged on for years.

this sweeping and accountability-free Bill winds up making the cure far worse than the symptom. The government’s tendency to focus on protestors and political opponents using surveillance techniques implies that the danger this Bill poses is solely too great.

Empowering police and governments to conduct such intrusive investigations in such an arbitrary manner, targeting whomsoever they choose with little accountability and few legal guidelines, won’t make Indians safer.